Publication date: June 27, 2023

Author’s note: Product teams at Meta rely on research along with other factors to design and build products. This article discusses research conducted by Meta's User Research Team to better understand people’s supervision and privacy needs. The author would like to thank her colleagues for their contributions to this project and related research: Ayca Cakmakli, Dan Busso, Carolina Milesi, and Jasmine Williams.

Abstract

To inform the design of Meta Family Center, we wanted to learn more about the kinds of online supervision tools that would be most useful for families of teens.

We surveyed parents and guardians* of teens in seven countries to learn which online supervision strategies they use today and which they think would best suit their needs. We also surveyed teens themselves about their impressions of the supervision they receive and openness to online supervision tools.

Strategies that allowed for some oversight while also supporting teen’s needs were generally preferred by both parents and their teens. This finding has implications for the kinds of parental supervision tools and educational resources that apps might prioritize creating.

* Throughout the remainder of the article, we use the term ‘parents’ to refer both to parents as well as others who serve as legal guardians of teens, such as step-parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles.

Report

As teens use apps and other online experiences, they can sometimes benefit from supervision and guidance to ensure they are using these products safely, responsibly, and in a way that facilitates their privacy (Busso & Sauerteig, 2022; Menon, 2021). In-app supervision tools are an important option for helping parents support their teens towards these goals. It is important, however, to design these tools so parents can easily and effectively be involved and so their teens are open to receiving this supervision.

To achieve these goals, at Meta we’ve been partnering with young people, parents, and experts from around the world to better inform the supervision tools and resources that our products offer. As part of that process, we surveyed 13,273 parents and their teens from seven countries (United States, United Kingdom, France, Brazil, India, Indonesia, and Japan). Survey respondents were asked about their experiences and needs with online supervision for teens. We were specifically interested in learning how prevalent it is for parents to have challenges with online supervision and support of their teens, what types of tools might best meet their supervision goals, and teens’ openness to these tools. For additional research method details, see the appendix.

What we found

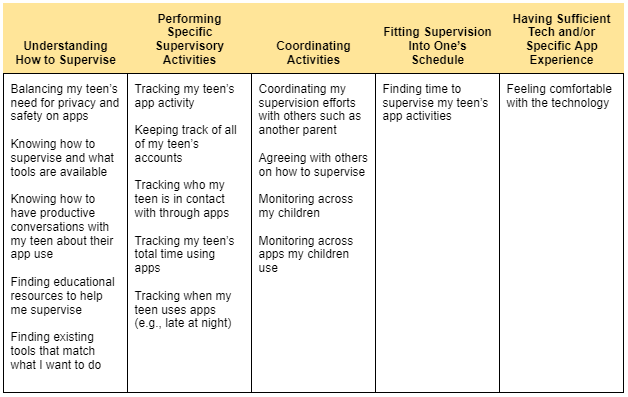

80% of the parents in our survey indicated that they found at least one aspect of online supervision of teens very or somewhat challenging for them (not specific to Meta’s apps). The types of tasks they found most challenging (reported by at least half of parents) included monitoring who their teen was in contact with and balancing their teen’s needs for privacy and safety. However, all key challenges surveyed were reported by at least one-third of parents, including identifying existing supervision tools and educational resources that meet their needs, knowing how to use these tools and finding time to do so, and coordinating across the children they supervise and with other caregivers. In other words, parents have a wide array of supervision needs (see Figure 1 for a categorized list of parents’ supervision needs).

Figure 1. Aspects of online teen supervision that parents reported as being challenging

To help with these supervision challenges, the majority of parents in our survey thought it important or essential for social media and messaging apps to add in-app supervision tools such as insights and settings (66%); educational resources aimed at parents such as suggestions for how to supervise and talk with their teen about online safety, wellbeing, and privacy (67%); and educational resources aimed at teens themselves (68%). Moreover, 68% of the parents in our survey who don’t currently allow their teens to use social media and messaging apps would consider changing their mind if such supervision tools were available.

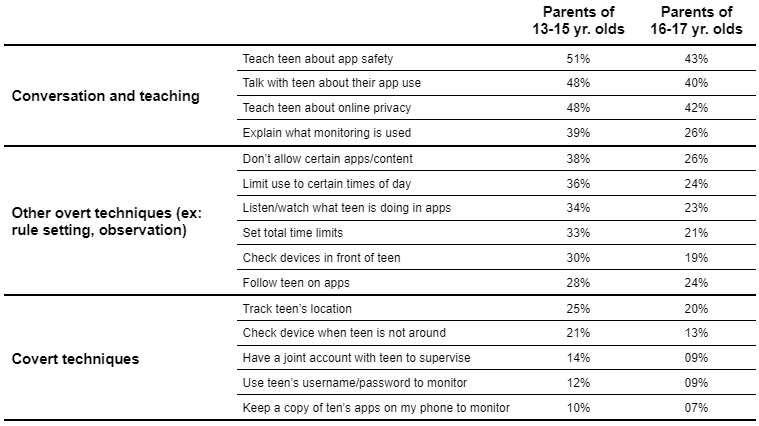

We also wanted to understand what specific supervision and guidance strategies parents were attempting to use today. To do that, we asked parents to indicate what strategies they had done for their teen in the past six months. We then grouped these strategies into three broad categories: (1) Conversation and Teaching; (2) Other Overt Techniques, aside from conversation and teaching; and (3) Covert Techniques, where teens are likely unaware when they are being monitored.

Table 1. Percent of parents who self-reported various supervision activities in the past six months (in general, not specific to apps from Meta or any particular company)

For all supervision activities in this table, parents of 16-17 year olds were statistically significantly less likely (p < .0001) to report doing the activity relative to parents of 13-15 year olds.

For all supervision activities in this table, parents of 16-17 year olds were statistically significantly less likely (p < .0001) to report doing the activity relative to parents of 13-15 year olds. Per Table 1, parents were most likely to report using Conversation and Teaching for supervision, followed by Other Overt Techniques such as rule setting. Covert Techniques tended to be less common, although 23% of parents did say they track their teen’s location and 18% report checking their teen’s phone when not around. The reported use of each technique across all three categories was also lower among parents of older teens.

These results suggest two things. First, although parents rely most heavily on dialogue and teaching, they also use a variety of other supervision behaviors. Apps therefore may need to offer a range of supervision tools to support different parents and their specific needs. Second, supervision tools may be more useful at certain stages of a teen’s development relative to others. Specifically, some parents may view teens as “aging out” of the need for certain overt or covert techniques over time. This finding is aligned with other research showing that parents often change the kinds of involvement and supervision strategies they use as their children age (Menon, 2021). Supervision tools ideally should provide families with the flexibility to adjust their support offered as their teens mature and gain experience.

Given the greater reported emphasis on Conversation and Teaching, it seems that many parents prefer supervision strategies that support teen autonomy, understanding, and transparency. Consistent with this point, the majority of parents in our survey indicated that they are at least somewhat likely to give their teen(s) some freedom to learn for themselves when using apps (66% for those with 13-15 year-olds, 70% for those with 16-17 year-olds).

Teens themselves may also be open to parental use of age-appropriate supervision tools provided they emphasize Conversation and Teaching. For instance, most teens in our study (92% of 13-15 year olds, 80% of 16-17 year olds) indicated that if their parents asked, they would consider participating with supervision tools for social media and messaging apps to facilitate conversations about their safety and wellbeing. Most teens (82% of 13-15 year olds, 74% 16-17 of yr olds) were also open to having their parents see and take action on at least some insights such as their followers/following list, purchases, and whether their account was public or private - provided their parents explained why doing so was important. These findings further suggest the importance of facilitating conversation and transparency with supervision tools.

Opportunities

In summary, our findings suggest that apps might be able to best support parents and teens by providing (a) multiple supervision resources so parents can select ones appropriate for their own specific needs and parenting styles, which may vary as teens get older, and (b) resources that primarily focus on overt techniques (including conversation and teaching) and transparency. Such techniques may help parents balance a need for supporting their teens’ autonomy with supervision and for building understanding and trust with their teen. We’ve also found similar themes during qualitative co-design sessions across 10 countries with teens, parents, and expert consultations (see Co-designing with teens and parents for online supervision).

At Meta, we’ve been taking steps to provide these kinds of resources to help families manage and support their teens’ use of Meta apps and technologies:

- In 2022, Meta launched Family Center, a central location for parents to access tools and resources to supervise teens. Family Center includes tools that provide parents with helpful insights and settings for their teens across Instagram and Virtual Reality (Quest) contexts, such as daily time use, follower/following lists, and a list of downloaded apps. By displaying age-appropriate supervisory information in a central location, parents are able to provide teens with useful support without having to use more invasive strategies such as going through the teen’s devices.

- Additionally, Family Center includes Education Hub, which is a site for families to access helpful instructional materials that were developed in conjunction with various advisors and policy organizations such as the National Association for Media Literacy Education (NAMLE), Parent Zone, and Connect Safely. We have also convened with leading experts in monthly Youth Advisor Council sessions where we have discussed issues of parental supervision, balancing teen privacy and safety, and tackling topics of overall youth safety and wellbeing. We also co-host roundtables with Boston Children's Hospital's Digital Wellness Lab. In these roundtables, we focus on immersive VR experiences and discuss foundational considerations of child safety and parental supervision with health experts. We’ve used these forums to help inform the kind of instructional materials we ultimately provide via channels like Education Hub.

By supporting a range of supervision strategies, we’ve designed these resources in a way that provides parents with flexibility and choice. Ultimately, parents know their own and their teens’ unique situations best; resources like Family Center and Education Hub can help them to support their teens online while also promoting their privacy on their path to adulthood.