Publication date: 07/13/2022

Author’s note: Product teams at Meta rely on research along with other external factors to design and build products. This article discusses research conducted by Meta's Research Team to better understand people’s privacy needs.

Abstract

We conducted research with 54 households in the US, India, and Brazil to explore digital education needs among teens (13-17 years old) and their adult caregivers.

Teens’ digital privacy education is a journey. It can’t be accomplished through a one-time lecture or tutorial. The knowledge, skills, and dispositions that teens need to develop come from a mix of instruction, direct experience, repetition, and reflection that happen over time and across a range of contexts.

Teens and caregivers often rely on different sources to gain privacy information, which leads each group to focus on a slightly different set of privacy topics.

Report

When people begin using apps and other digital services in their teenage years, how do they learn about privacy? And what can others do to help them acquire the knowledge and skills they need to have a safe and healthy relationship with digital products?

According to Common Sense Media, effective digital education requires people to not only gain knowledge about a topic but also to gain relevant skills and dispositions (James, Weinstein, & Mendoza, 2021). Knowledge is what someone knows and believes, skills are what someone knows how to do, and dispositions are tendencies that guide how someone applies their knowledge and skills. When someone successfully gains all three of these components, they’re more likely to feel a sense of mastery and to be able to successfully navigate their digital experiences.

So how do teens acquire knowledge, skills, and dispositions for digital privacy today, and how can others help them on that journey? To begin answering this question, we conducted research with 54 households in the US, India, and Brazil to explore digital education needs among teens (13-17 years old) and their adult caregivers. The research included video diary sessions with teens, 1:1 interview sessions with teens and their caregivers separately, and group interview sessions with teens and their caregivers together. For additional research method details, see the methods appendix.

What we found

The teen journey

The teens we spoke to developed their knowledge, skills, and dispositions for digital privacy through a combination of instruction, direct experiences, repetition, and reflection (cf. Agosto & Abbas, 2015; James, Weinstein, & Mendoza, 2021; Kumar et al., 2017).

Figure 1. Teens in our research learned about privacy through four main pathways.

The teens in our research didn’t tend to seek out digital privacy education spontaneously for the sake of learning about it. Instead, they would learn about privacy when an opportunity presented itself, either because someone decided to discuss digital privacy with them or in response to a specific need or experience the teen encountered while using an app.

An important early source of knowledge and skills for our participants was direct instruction that they received through conversations with parents, siblings, friends, and other people in their lives. Caregivers such as parents were often the ones who initially taught their teens about basic privacy concepts and skills through conversations they initiated about this topic.

However, the teens in our study seemed to primarily learn about digital privacy through their own experiences of using apps. For example, one teen expressed that he believes the only way to really learn what content he should share online is through practice — by posting different things, observing reactions to his posts, and deciding if he likes the outcomes. Another teen described how he observed the ways his friends would use Instagram and then change his own behavior to match what they did. A third teen told us about an experience where he and his friends learned about respecting each others’ digital privacy as a result of an online prank.

These examples illustrate an important point about teens’ digital privacy education: Direct experience using apps can be a critical component for how teens learn about what to do or not do online. Exploration in particular seemed to be an important part of how the teens in our study ultimately internalized important knowledge, skills, and dispositions. For example, one teen described how she learned from her mistake of clicking on a link that led to her account being hacked; as a result of that experience, she’s now more committed than before to avoiding unknown links. These kinds of examples suggest that teens could benefit from opportunities to experiment and build their confidence about digital privacy in contexts where mistakes don’t result in long term negative consequences.

In our discussions with participants, we also heard that repetition was important for teens to really internalize skills and dispositions about digital privacy and related topics. Sometimes lessons need to be repeated or experienced more than once to leave a lasting impression.

Finally, we also discovered that teens sometimes need opportunities to reflect on their digital privacy experiences to build strong dispositions for how to act in the future. Reflection sometimes happens alone (someone thinking about their own past experiences) and sometimes as part of discussions with trusted adults or peers. Over time, opportunities for reflection can help to create healthy habits and dispositions to help teens proactively address scenarios they may face in the future.

Overall, our research revealed that teens’ digital privacy education is a journey. It can’t be accomplished through a one-time lecture or tutorial. The knowledge, skills, and dispositions that teens need to develop accrue over time and in response to different kinds of experiences they have.

The caregiver journey

When thinking about how to deliver effective digital privacy education to teens, it’s useful to understand the perspectives of people who teens trust to teach them about privacy. In this research, we found that parents and other caregivers are one of the most significant initial sources of knowledge and skills in teens’ digital privacy education journey.

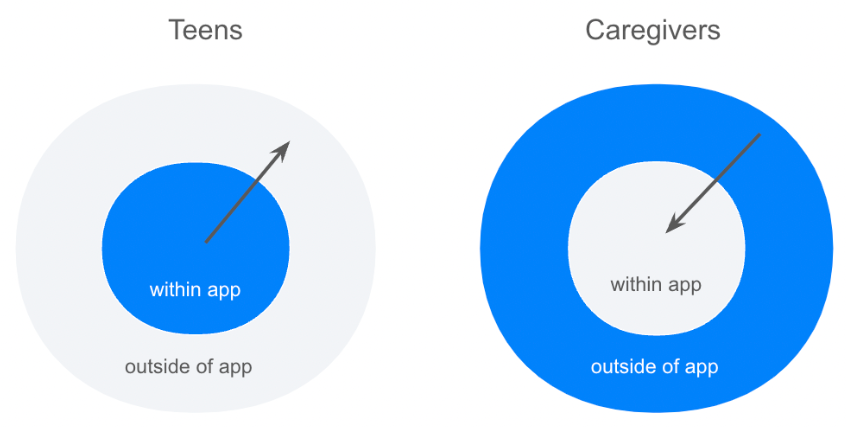

Interestingly, the teens and caregivers in our research seemed to rely on different strategies to learn about digital privacy: The teens learned from the inside-out, whereas the caregivers learned from the outside-in.

Figure 2. Teens and caregivers in our research relied on different learning strategies.

Whereas the teens in our study tended to rely heavily on their own experiences to learn about privacy, their caregivers tended to rely more on information about privacy from the media, from stories shared by their peers, and from their own offline experiences.

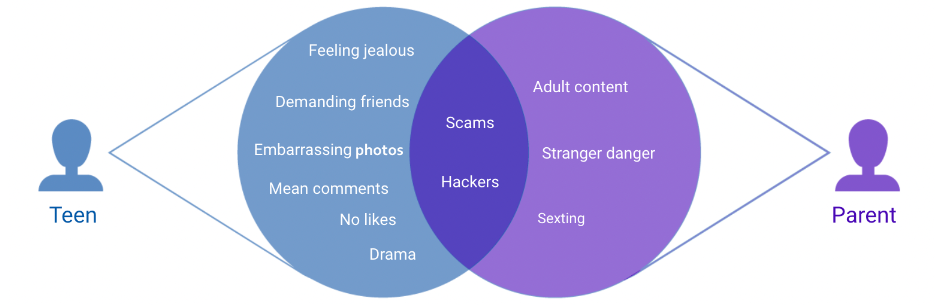

One consequence of teens and caregivers relying on different sources of privacy information is that each group tended to be concerned by a slightly different set of privacy topics. The privacy topics that were most important to teens (stemming from their personal experiences) were often not the same topics that their caregivers felt were most important to discuss (stemming from what they heard about in the media or from peers). By relying on different sources of privacy information, teens and their caregivers sometimes had a gap in understanding or agreement about what was really important for the teen to learn about. For example, while caregivers believed that topics such as adult content, “stranger danger,” or “sexting” were among the most important privacy topics to address, teens were more likely to emphasize topics such as embarrassing photos, mean comments, or not getting enough reactions to their posts.

To the extent that caregivers and teens are misaligned about the privacy topics that are important to discuss with each other, it can create a situation where (a) teens may pay less attention to the privacy information their caregivers share with them because they don’t view the information as useful or important and (b) teens may not get sufficient caregiver support about the topics they’re actually struggling with. By helping caregivers to identify the topics their teens are most likely to want support with, it may be possible to empower teens’ social support networks to help them navigate digital privacy more effectively.

Figure 3. Teens and caregivers in our research tended to focus on different privacy topics.

Figure caption: These are topics that the teens and caregivers in our research focused on when discussing privacy.

Opportunities

Based on these insights, we believe that app developers have at least three opportunities to help promote digital privacy education among teens. The first is to develop ways to help teens mindfully reflect on their digital behaviors more broadly. At Meta, we’ve begun to explore this opportunity through features such as “take a break” on Instagram, which is an opt-in control that enables you to receive break reminders after a duration of your choosing. This feature can help people become more aware of how they’re using products like Instagram and to reflect on how they want to use them.

The second opportunity is to provide teens with age-appropriate experiences. For example, some privacy experiences on Instagram, Facebook, and Meta Quest are different for users under the age of 18 (Teen Privacy Explained). These experiences include who can see their profile (e.g. profile automatically set to private upon sign up), ads (e.g. advertisers have fewer options when showing ads to minors), and supervision tools available to parents and guardians to support teens.

The third opportunity is to provide resources to caregivers to help them connect with and support the teens in their lives when it comes to digital privacy education. At Meta, we offer this type of guidance through channels like the education hub on our Family Center, which provides caregivers with resources, tips, and articles from subject-matter experts and trusted organizations to help support their teens’ experiences online. For example, we've been developing conversation and discussion guides that can bridge teen and parent perspectives about which privacy, safety, and well-being topics are useful to discuss with each other in order to facilitate healthy dialogues.

Conclusion

Teens’ digital privacy education is a journey. It can’t be accomplished through a one-time lecture or tutorial. The knowledge, skills, and dispositions that teens need to develop happen over time and in response to different kinds of experiences they have. Parents and other caregivers can play an important role in that journey by helping teens develop their knowledge and skills, as well as reflect on meaningful privacy experiences that they have.