Authors’ note: Product teams at Facebook rely on research along with other external factors to design and build products. This article discusses research conducted by Facebook's Privacy Research Team to better understand people's needs related to privacy settings.

Abstract

Based on a series of user research studies, Facebook’s Privacy Research team identified two important strategies that help make privacy settings easier to find: (1) Present privacy settings in short lists that are grouped based on users’ mental models for privacy topics. (2) Use descriptive names for privacy settings that avoid the generic word “privacy”

In this article, we also discuss the potential impact of industry standards and iconography on consumers’ ability to easily find privacy settings.

Report

For people to have positive privacy experiences when using an app, companies not only need to include the right privacy settings, they also need to ensure those settings are easy to find. At Facebook, we hypothesized that we might have an opportunity to make our settings easier to find for two reasons. First, over the past several years, the Facebook app has evolved to include many new features, which has greatly expanded the number and types of privacy settings that exist in the app’s settings menu. Second, consumers’ expectations for which privacy settings exist in Facebook, what they’re called, and how to find them may have evolved over time, not only based on their use of Facebook itself but also based on their use of other products that may design privacy settings differently.

To ensure that our current privacy settings are as easy to find as possible, Facebook’s Privacy Research Team has been conducting a series of user research studies over the past year with methods that include card sorting, ethnography, usability testing, and heuristic evaluation. What we’ve learned has changed our approach to designing privacy setting menus, including the way we present menu options and how we structure navigation within menus. In this article, we summarize some of the key insights coming out of this work that we believe have implications not only for Facebook but also for other apps and companies.

The importance of short lists that are grouped based on mental models

Consumers expect apps to have a wide range of privacy settings so they can customize their own experiences in an effective way. However, through the research we conducted, we discovered that some of Facebook’s privacy setting menus had become so extensive that it could be challenging to find specific individual settings, partly due to the cognitive load of searching through long lists of options. Moreover, some research participants felt a sense of information overload when looking through long privacy settings menus, which could potentially lead some of them to give up before they found a setting they were looking for.

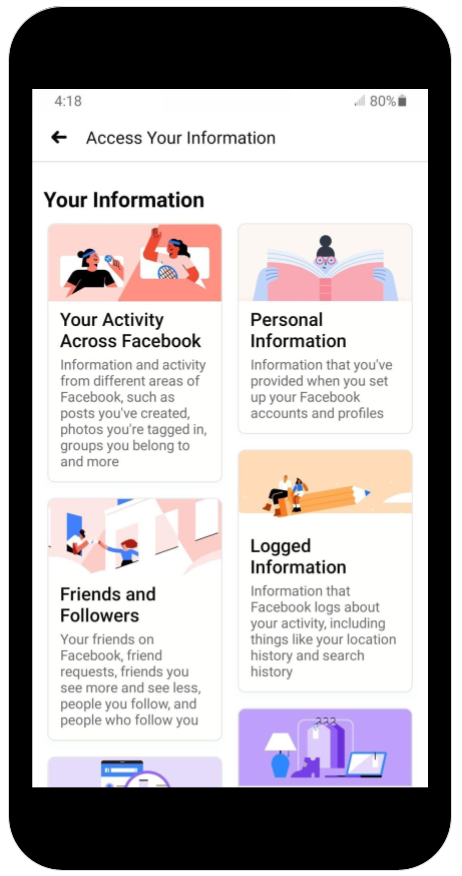

To address this, we’ve begun to organize privacy settings into groups to reduce the size of the initial menus and make those menus easier to navigate. We’ve found that a good way to create effective groupings is to consider users’ mental models about which settings are related (mental models refer to users’ beliefs about how a system works). For example, Facebook’s Access Your Information (AYI) feature lets people view and manage over 100 data types within Facebook. An early design idea for AYI organized the 100 data types into 23 data categories. Through research, we learned that even 23 categories was too many for this feature. When we conducted card sorting studies to learn how participants would categorize these data types themselves, participants consistently created 10 or fewer categories, and those categories were consistently made up of settings that addressed similar privacy topics. For example, participants tended to group all settings about profile information together in one category and all settings about the audience or visibility for their content into another category. Based on that research, we revised the number of data categories in AYI to 10 and grouped settings into categories based on the privacy topic they were addressing. This has made it easier to find individual data types and also reduced the sense of information overload some participants could experience when using AYI.

Insight: Privacy settings can be easier to find when they’re presented in short, well-organized menus. Grouping settings based on users’ mental models about which privacy topic(s) the settings address can be even more helpful.

The importance of descriptive names that avoid the word “privacy”

A principle often used when naming things is to keep the names short. There are a number of benefits to short names - they can “pop out” when you’re looking for them, they can be easy to remember, and they’re easier to fit on the screen of a mobile device. Those are all outcomes that should make a setting easy to find. However, through our research we learned that in some cases short names for privacy settings actually made it more difficult for participants to find the settings they were looking for because the names weren’t sufficiently descriptive, particularly when there were multiple related settings available. As a result, participants in our research studies would sometimes overlook the setting they were seeking because it wasn’t clear from the name alone that it was the option they wanted to use. For example, when research participants attempted to manage the information that Facebook receives about them from other websites, some participants would overlook the setting “Your Apps” because they weren’t clear that it would contain information from websites. When we changed the name of this setting to be more specific and descriptive (“Apps and Websites”), we were able to make it easier for people to find despite using a longer name. We found similar results when we tested more specific and descriptive names for a range of other settings - for example, naming a setting “Your Activity Across Facebook” rather than “Posts” made it easier to find.

Figure caption: An example of one design we explored that includes specific and descriptive names.

Surprisingly, we learned that including the word “privacy” in a privacy setting name was often counterproductive and could make it harder to find. The word privacy doesn’t have a single, universal meaning, but instead is interpreted in different ways by different people (e.g., Hepler & Blasiola, 2021). So when privacy is used as a category name in a settings menu, participants often had mixed expectations about what the settings in that section of the menu would do. When we replaced the word privacy with more descriptive language related to specific privacy topics, the privacy settings became easier to find — for example, naming a menu section “Audience and visibility” instead of “Privacy settings”.

Insight: Privacy settings need specific and descriptive names to ensure people can easily find the settings they want to use. In some cases, this will require using longer rather than shorter names. Ironically, avoiding the word “privacy” itself often makes settings easier to find.

Open questions and other potential opportunities

Standardized settings. Different people can have different assumptions for how to find the same privacy setting — including where to look and what names to look for. Academic researchers have noticed that this is true across a range of apps and websites beyond Facebook (e.g., Habib et al., 2020). This may be partly attributable to the fact that people’s mental models for how to find privacy settings will be influenced by how those settings are designed in the products they’re most familiar with. So to some extent the ability to find privacy settings may always remain a challenge for some consumers if different apps and websites use different locations and names for equivalent privacy settings. One key opportunity for the tech industry as a whole is to begin moving toward standardization for the design of privacy settings, particularly with respect to the names and locations of those settings. This may not be as simple as it seems for a variety of reasons — for example, some privacy settings aren’t applicable to all apps, and omitting those settings will naturally impact the way lists and groups of settings can be designed in a given app. However, to the extent that cross-industry standardization is possible, we believe it’s a promising strategy to explore to help consumers more easily find privacy settings.

Visuals and iconography. Theoretically, it should be possible to use visuals and icons to help consumers easily find privacy settings. This may be particularly helpful in a world where privacy setting menus have more text due to using specific and descriptive names. Although we’ve begun exploring how the use of visuals and icons may help make it easier to find settings, we’re in the early stages of this exploration. Similar to academic research on this topic, so far we’ve found that visuals and icons contribute little above-and-beyond text descriptions when it comes to helping consumers understand privacy settings (e.g., Cranor & Schaub, 2020). However, we believe this is an area that’s worthy of continued exploration.

Conclusions

When using apps, consumers’ ability to have positive privacy experiences can be dependent on how easy it is to find privacy settings. Based on our research, companies can make privacy settings easier to find if they (a) present settings in short lists that are grouped based on users’ mental models for privacy topics and (b) use descriptive names that generally avoid the word “privacy”. In our experience, the best way to determine the right list size, groupings, and names is to collect user feedback in order to test and validate different options. We believe that by using this approach, companies can ensure their privacy settings are easy to find and therefore best positioned to support positive privacy experiences for their users.